What makes someone special?

Born into wealth? A terrific athlete? Good looking? A celebrity?

Unquestionably, people have many reasons for calling someone special. My Mom, my wife, my children, the Vet that saves my dog’s life. My dog, not necessarily someone, but still special in so many ways.

How about the child born homeless in the Ugandan forest during the Ugandan civil war? This is Sanga’s story.

This story is just too incredible to believe, but it is true. I want to share it because I want you and everyone who believes in the GIF mission to hear it. I have no expectations that everyone should be a Sanga Moses, but when I am done I think you will agree that the world would be a better place if they followed Sanga’s example. I apologize for being long winded, but there is just so much to share.

Simply stated, Sanga’s passion is off the scale. It is hard to understand what internal drive makes him this way. His outward demeanor is so gentle, even reserved, imbued by a humility that makes me envious. His life story seems like a fictional perfect for a feature film.

Sanga picked me up at the Banda Inn in the Myeunga District in Kampala at 9 a.m. on January 20th for the drive through Kampala to their offices near Lugazi about 90 minutes outside the city. I knew immediately there was no pretense in this guy. His car, a 1980 Toyota, covered in dust, inside and out, with a side door that would not open and no air conditioning which explains the dust inside was barely drivable. The windows had to remain open or you would cook inside. Suspension was non-existent. Ugh! On the way out the Inn gate the guard pointed out an almost flat tire. Sanga was obviously not spending any money on non-essentials. He was happy to have a vehicle. Here is why.

In route I started asking him about himself. ”Sanga, how old are you?” His response set the stage for this story.

“I tell people I am 32, he said, but, I really do not know. My parents were forced to live in the jungle for four years during the civil war and I was born there. They were illiterate and did not know. They did not know what a calendar was or a clock or the concept of time other than the rhythms of nature. They were nomadic cattle herders before the war working for someone else moving their cattle to wherever they could feed. They were too poor to own anything and lived in the fields with the cattle fashioning makeshift huts as temporary housing. When the war broke out they fled to the forest where I was born.

My mother named me Sanga which means horn or elephant ivory. I have a little sister but after the war she died when she was ten from complications with her health after surviving measles and then contracting polio. I tell people that I was born on June 1, 1982 because I could not go to school unless I gave the authorities a birth day. So, I am 32 or 35 or 28. It doesn’t matter anymore. When the war ended I was probably around two years of age. I do not remember the forest, but this is what my parents told me.

They left the forest and tried to go to their home to find work again as cattle herders. I remember this. This is what my grandfather and great grandfather also did. But, it was not possible. The government forced all the refugees into a specific area. We were displaced again and ended up in rural southwest Uganda. We had nothing. This is the life we lead and my parents told me it was a good life to be a cattle herder no matter where you were.

I learned a lot from my parents. I learned what it was like to be hungry. My mother told me that my grandfather and great grandfather never ate food in their entire life except for a few times. As a cattle herder the owners would allow them to milk the cows. So they had some milk. Their primary food was cattle blood. My grandfather would use an arrow to puncture a bull’s vein in his neck to take blood but not harm the bull. He would boil the blood until it became thick like a paste and this is what his family, my mother and father had for food when they were growing up. Milk and boiled cattle blood. On rare occasions when an animal might die they slaughtered it before it became too sick. Maybe it was a cow. Sometimes a goat. It was a rare delight. They could smoke the meat and it would last for about two weeks. Most of the dead animal was left to the scavengers because there was no way to keep it all before it went bad.

After the war, my father wanted to return to the job as a cattle herder, but he could not do it where we lived because the government forced all of the refugees to move to southwest Uganda. There he found a job herding another man’s cattle and they made an agreement that if he did a good job one day he would be rewarded with a calf of his own. You have to understand, everyone was in the same situation. No food, no home, no future to speak of. In fact, my father thought this was a good life because he knew of nothing else. It was 1987.

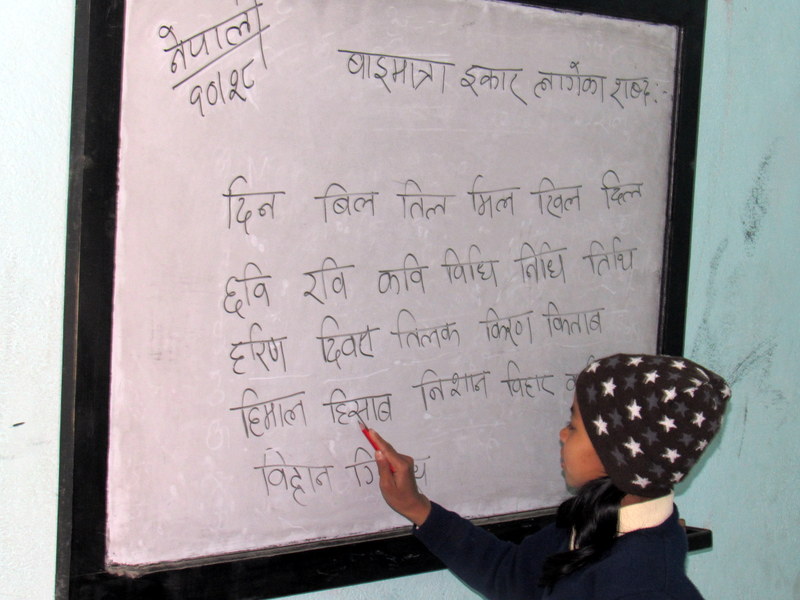

Then the Missionaries arrived. They told all of the people just like us that their children should not be in the fields with the cattle. They should be in school. So, my Mother sent me to the small village nearby to attend school which was held out in the open. There was no building. The missionaries had one blackboard. That was all. But we went every day.

At the school I was able to get good grades and then the government showed up and declared that the top students would be sent to government boarding schools. Each term I did well enough to get promoted to the next level and at one point the government decided that I should go to university on a scholarship. I had never been away from home and now they wanted to send me to Kampala. I was afraid and for good reason. Kampala was a crazy place. I had never seen such huge buildings and so many people. I did not want to leave the room they put me in but I didn’t want to be in the room either. I was 17 and had never lived indoors ever. It was very strange and I cried a lot. I was able to visit my parents and my father always told me to come home, be a cattle herder. It is a good life. But my Mother wanted me to stay in school. So, I did.

I graduated with a degree in accounting and was offered a job in a bank. For the first time in my life I was able to earn money and bring it home to my parents. My father never understood how I made money, but when he saw me come home in a tie and jacket he was proud. (Sanga said he was very lucky because many boys much smarter than him were passed over.)

I worked at the bank for four years. While I was there my father left my mother. He was older now (in his 40s is old in Uganda) and having a very difficult time getting by. My mother remarried to a man with six children. One day I went home to visit my family and on the road to my village I saw my step-sister carrying a load of firewood who was supposed to be in school. I asked my Mother why she was not in school. She said she was an old woman and if she was in school she would have to collect the firewood for cooking and she could not do that anymore. So, my little sister had to skip school twice a week to collect firewood. I had saved some money from my job and I had heard about solar cookers, so I took my savings from the bank and bought a solar cooker for my mother. But, the next time I visited she was still cooking their beans on the traditional three stone fireplace. She said the solar cooker did not work. It had to be set up outside during the day. You cannot use it at night. And if the wind blows dust is everywhere and that ruins the beans. I needed to do something so my sister could stay in school. I went back to Kampala and began to research ways to displace the need for firewood and I came across this ides for converting biowaste into briquettes which we call today at Eco-Fuels “green charcoal” so the traditional people will not be so afraid to try it and abandon regular charcoal which in embedded in the Ugandan culture. I took the rest of my savings to buy the parts to build a briquette making machine. But I was an accountant and knew nothing about how to make a machine. It failed, but I thought I was so close and I could not give up now. So I sold everything I had in my apartment except my bed to raise more money. I convinced five of my friends to join me. I went back to the University and found a professor that taught environmental studies and asked for his advice. He said he had a large library of literature that I could use, but otherwise had no money to help. I spent weeks reading about alternative ways to cook food. Biowaste briquettes were quite common, so I decided to try again. I took all of my money, bought a briquette machine and learned how to make char that could be made into briquettes. I bought a cookstove and gave it to my mother along with the briquettes and that was the beginning. My sister could now go to school all of the time.

Of course, I am abridging and paraphrasing this story a little, but it is reasonably accurate. I needed to get it down in writing before I forgot too many of the details. Sanga, born in the forest, raided by illiterate cattle herders and willing to risk everything to help his little sister has a degree in accounting and a PhD in life. He is so incredibly upbeat. Thinks nothing is an obstacle. He is gracious, humble and has a vision to help those even worse off than he was as a boy.

Today, five years later Sanga is the leader of a successful social enterprise that employs about 40 people in four locations, all who have been severely marginalized. He has built a network of micro-entrepreneurs, all women, all with at least one daughter, all severely marginalized as well. These women sell the briquettes at a kiosk which Eco-Fuels leases to them that they are able to pay off within three or four months because the demand is so strong. He has built a network of 1500 farmers that supply the biowaste to make briquettes in each of the four communities. He has a vision that one day he will have thousands of micro-entrepreneurs selling “green charcoal” in communities all over the southern part of Uganda. He knows that to do that he needs the support of about 250 small farmers to produce the char required to meet the briquette demand for each community and roughly 250 micro-entrepreneurs to sell the product. Now, he has a plan to bring into the mix 10,000 boys who have no jobs, no opportunity to produce the char from the biowaste the farmers provide. He told me these boys will be the next child soldiers for military fanatics if something is not done to provide them an income. His success has drawn the attention of the local and central governments. An Indian businessman, one of the richest men in Uganda worth over $900 million invited him to a meeting where he offered Sanga $1 million to sell his business and a ten year contract to be its CEO. He turned him down. He said to the businessman who he feared, “How can I do that? Everyone around me is poor. How can I do that?”

In short, nothing is impossible if you believe. Sanga is a living example. Five years after buying the solar cooker that failed, the first briquette machine that also failed his company employs many dozens of people earning at least minimum wage. All of the micro-entrepreneurs are women with no husband (died or left the family). In order to be a Eco-Fuels micro-entrepreneur there has to be one daughter at a minimum in the family that is in school. I met several of these women and they all said the same thing. They can now feed their family and send their children to school.

That is Sanga’s story. I do not care what anyone says. If you spend any time in Uganda you quickly realize there is virtually no infrastructure outside of Kampala and it is kind to say there is any of substance in Kampala. There is no one to lean on. Yet, in spite of the challenges Sanga has already done some remarkable things.

As Sanga and I drove around a village surrounded by an enormous sugar can plantation and worked by the very poor I noticed a barefoot old man walking on a rutted rocky road not even suited for a car, motorbike, let alone a barefoot old man struggling uphill. I mentioned to Sanga how difficult that must be to live a barefoot life in abject poverty in such difficult conditions. Sanga turned to me and said, "Ken, it is very common. I did not hasve as pair of shoes until I was 12.."

Again, this is Sanga's story. It is humbling.